Leslie Adkin: Farmer Photographer

A superb selection of the work of one of New Zealand’s finest early photographers.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Athol McCredie, author of Leslie Adkin: Farmer photographer, discusses his book with Te Papa Press.

Athol McCredie is Curator Photography at Te Papa, where he has worked since 2001. He has been involved with photography as a researcher, curator, and photographer since the 1970s. His publications include Brian Brake: Lens on the world (editor, 2010), New Zealand Photography Collected (2015) and The New Photography: New Zealand’s first generation of documentary photographers (2019).

Athol McCredie. Photo by Yoan Jolly. Te Papa

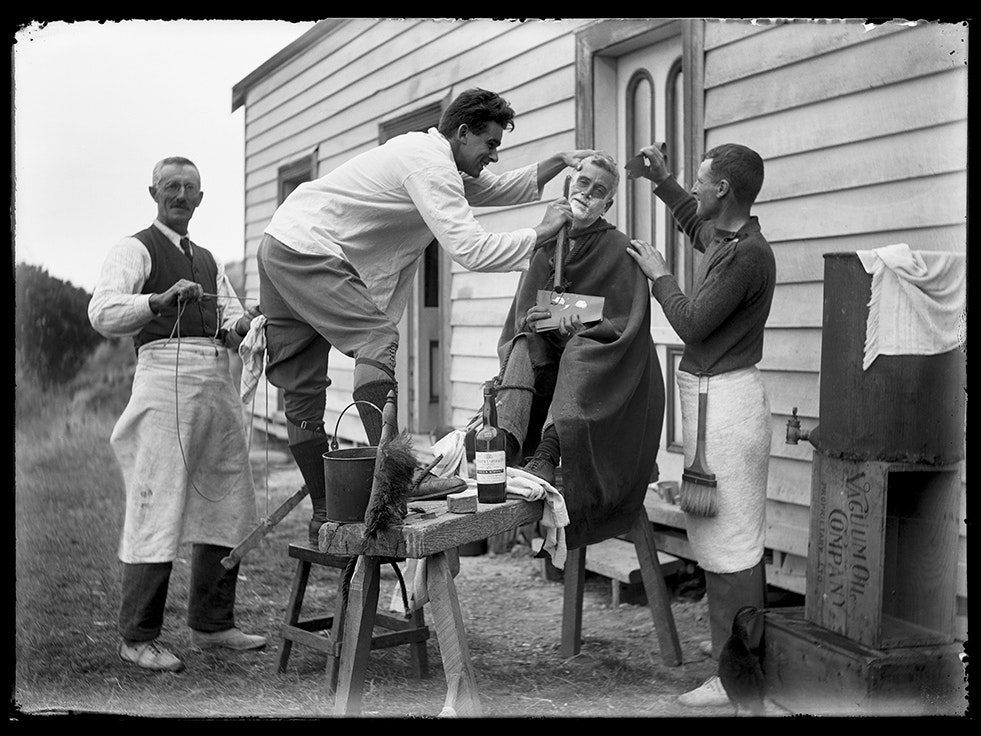

Their charm. I love their humour, the enjoyment his subjects seem to have of life, and the consistent cast of family and friends over time. The images depict an idyllic lifestyle of a large, fairly well-off family having fun at picnics, beach outings, travel, and entertainments at home.

Then of course, at the core of Adkin’s photography is a love story focussed on his wife Maud. I’m not the first person to have vicariously fallen in love with Maud through Adkin’s photographs.

Not really. In the nineteenth century there were the gentlemen amateurs, and in the 1960s and 70s there was the emergent generation of documentary photographs I’ve written about in my book The New Photography. Eric Lee-Johnson was wide-ranging in photographing the world around him in the middle of the twentieth century too. The work of these photographs shares some commonalities with Adkin’s, but there are also differences. More comparable photographs were taken in Adkin’s own time, but none of their creators produced anything like such a large and consistent body of work as his. Adkin really applied himself to everything he did, including to his photography.

Yes. He was using glass plates up until about 1930. They were inserted into the camera within double-sided wooden plate holders. All that glass and wood was both heavy and bulky and he only got twelve shots from his six plate holders before he had to reload them in a darkroom. On his 1911 crossing of the Tararua Range his camera gear weighed over seven kilograms. He shot a total of twenty-two photographs on this trip, so he obviously took along extra plates that he reloaded in a light-proof bag or under a blanket at night.

His plate cameras, particularly the half-plate one, were generally mounted on a tripod when he took a photograph. So he would have needed enough flat ground on which to set up a tripod. Even with a tripod, photographing in a wind – for which the Tararua tops are notorious – probably wasn’t possible. And just taking a single photograph was quite a trial. The camera had to be unfolded, the tripod set up and the camera levelled, the scene framed and focussed under a dark-cloth, the exposure estimated and shutter and aperture controls adjusted, and then the plate holder inserted and the dark slide removed. All before releasing the shutter. It would entail several minutes, so he couldn’t take photographs on the go.

I think he always photographed her with love, and the way she looks back shows her reciprocated feelings. She was clearly endlessly patient with his desire to photograph her, given how time consuming setting each shot up was. And also so willing: you could argue that these hundreds of photographs were collaborative efforts, made by Maud as well as Leslie.

The effort to set up each one, as I’ve mentioned. And lack of control. The latter includes having to deal with the vicissitudes of light, which might range from too harsh to not enough, and of working with people in informal contexts. The studio photographer has a social contract with his or her customer that requires them to obediently follow directions. In working with family and friends Adkin didn’t have this – though he was pretty good at imposing his will on his subjects.

That informality applied to personal contexts. So we see aspects of life that were not recorded by studio photographers or within any sort of public culture. Of course, snapshooters also took informal, personal photographs, but their cameras were usually poor quality and yielded tiny, fuzzy images. Adkin was using professional standard equipment and took a great deal of care with each shot. He was also going out of his way to record the everyday – Maud peeling vegetables, his sisters washing the dishes, his father and farm hands dipping sheep. Snapshooters tended to restrict themselves to ritualised occasions of holidays, outings, birthdays, and the like.

When you work intensively with a photographer’s collection you may be attracted to the ‘classics’ first off. But with over-familiarity you start looking for the less typical, the unknown, and the unexpected. So I started out loving the frequently published shot of Winnie Walker posed on ice plants in her bathing suit, or of Maud bathing Nancy in The order of the bath. They are great images, but personally I am done with them. Also, perhaps tastes have become more sophisticated since these photographs were first acclaimed back in the early 1970s. It is interesting that my Te Papa art curator colleagues, who are far less familiar with Adkin’s work, were excited as I was by my recent finds of Gilbert with the giant cauliflower, the Chairoplane carousel and, most of all, with the women lying on the sand in Sleeping beauties.

So, yes, Sleeping beauties. It is not a typical Adkin image in that it was taken unobtrusively, but it does have his sense of humour and keen observation. I love the incongruity of women in their best clothes lying on the sand. And the way it is such an off-guard, yet so human moment when everyone nods off with a book after a picnic lunch. Though some see dark undertones – voyeurism on the part of Adkin or a suggestion of some sort of atrocity (dead bodies in the dunes) – which make it a more complicated image.

I would like to think that readers’ hearts leap with delight when they open the book. As a person, Adkin may have been authoritarian, conservative, and severe, but his photographs display a love of being in the world and wanting to record it all. It is an upbeat book that depicts an (apparently) simpler, happier era – one to hold close in these more difficult and complicated times.

A superb selection of the work of one of New Zealand’s finest early photographers.

As part of her internship, Art History student Annie Barnard worked with some of the diaries and photographs from our Leslie Adkins collection. Here she talks about a trip to Kapiti Island that he documented.

A prolific diarist, photographer, farmer, ethnologist, and geologist, Leslie Adkin was also a romantic. Frequently a subject in Adkin’s photographs – either as the central focus or to show scale – his photography often tells the story of his great love of Maud Herd – from their courtship in 1910 to old age.