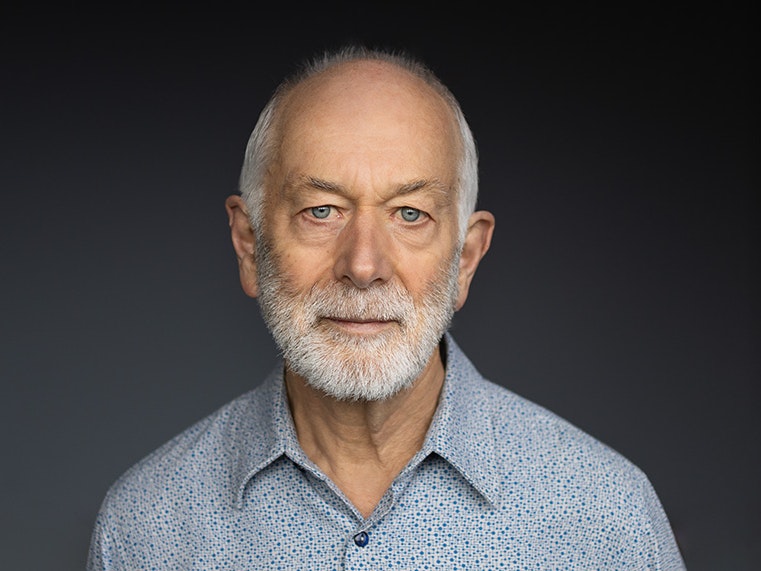

Q&A with Athol McCredie, author of New Zealand Photography Collected

Athol McCredie discusses New Zealand Photography Collected with Te Papa Press.

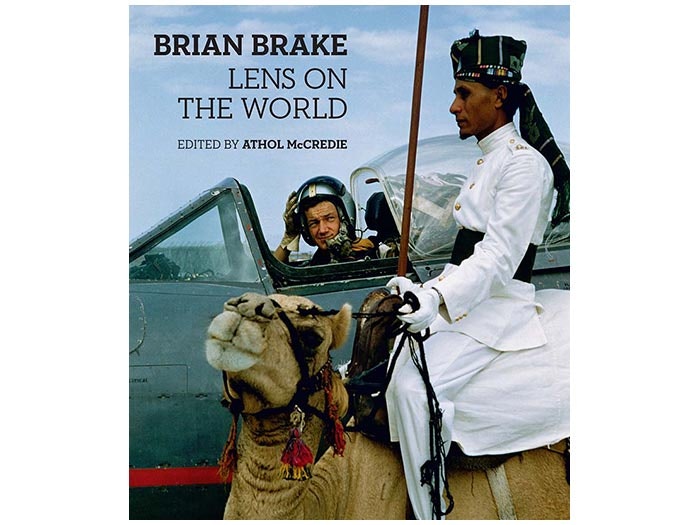

Athol McCredie is Curator Photography at Te Papa, where he has worked since 2001. Prior to that he was curator and acting director at Manawatu Art Gallery (now Te Manawa), and he has been involved with photography as researcher, curator and photographer since the 1970s. His publications include Witness to Change (co-authored with Janet Bayly, PhotoForum, 1985), Fields of Golden Daffodils (National Library, 1991) and Brian Brake: Lens on the world (Te Papa Press, 2010).

"The dream of photography – to stop time and cheat mortality – is as poignant as the dream of flight, to escape our earthbound limitations." – Athol McCredie

Tell us about Te Papa’s photography collection.

Well, it is large, consisting of an estimated 320,000 items. It is also unique in this country in its breadth of coverage. It includes collected photographs as well as work generated by museum staff over more than one hundred years. Both types tend to reflect the interests of the museum over this period, from natural history to Māori and Pacific cultures to social history and photography itself. On top of this, and this is where the combination is unusual, it also includes photographs collected as art. This is due to Te Papa being formed from the merger of the former National Museum and the National Art Gallery.

How many photographs are illustrated in New Zealand Photography Collected and was it difficult to choose?

There are 440 photographs in the book. And yes, of course it was difficult to whittle some 320,000 images down to 440! Actually, I’m overdramatising. For a variety of reasons my working start list was probably more like 80 – 100,000 images. I was familiar with big chunks of these already and also had figured out techniques for filtering large volumes of images. Getting down to a short list of 1,000 or so images was certainly very time consuming but not so difficult. The hard part was then leaving out so many good images to get to 440. There were many painful decisions, but in the end a lot came down to how one photograph worked with another on a page spread, or how the photographs functioned as a sequence in a book. You are working with visual narratives and while there were a few must-have’s, much of the selection was about making images work together. There was also a balancing of well published photographs against less known ones. So if some people wonder why certain iconic photographs weren’t included it may have been that I simply felt they had already had a good outing and it would be nice to show some fresh images.

What’s the most surprising thing you learned when writing this book?

There were great photographs I didn’t know we had. So I guess that was a pleasant surprise. And I learned that some close examination, and intense thinking and research can begin to unlock some of the secrets our photographs hold. For so many historical images there is little or nothing recorded and one tends to just accept that. But with a bit of detective work it can be possible to understand why a photograph was taken – that is, what its intended use was. Usually you never have time for this sort of thing, so it is really satisfying when you can unravel a bit of history and transform the way you think about a photograph.

Where and when do you write best?

At home in my spare room, with a cup of green tea to sip. I used to think that I worked best in the late afternoon, but that was just an excuse for procrastination. I find that any time of day is good provided I don’t have something like an upcoming meeting to keep an eye on. For this book I would often start before breakfast in order to get things moving early and use breakfast and the routines around it of showering, shaving and making the bed, as an enforced break.

Digital photography – is it a blessing or a curse?

For collecting it creates some issues, such as what the thing you are collecting actually is if there is no physical object but simply an electronic file. And having to come to grips with the fact that other institutions may collect the identical file. Digital also creates potentially unmanageable volume at times, because it is so easy to take such images and people rarely edit them. Then there is the concern about longevity. A negative from 1900 could still be printed in 2000, one hundred years later, but it is unlikely that we will be using the same storage, viewing and printing technology for digital images taken today in one hundred years in time. Some say that there is the risk of a digital dark age, a period in history (our own) from which few records will survive long term. You only have to wonder what happened to all those floppy disks that used to hold our information. Against all that, digital photography makes things so much more convenient: you can see your results instantly, you can adjust colour, density etc. easily, you can disseminate photographs so readily.

You are a photographer yourself. How do you balance your own photography with working as Te Papa’s Curator of Photography?

Well, I think it would be more accurate to say that I used to be a photographer – both of the exhibiting artist kind and later as a commercial photographer. But early on I found that working with other people’s photographs was more interesting than trying to make something inspired myself. And it was equally creative.

How do you see the role of photographers today, when everyone has a smartphone and an Instagram account?

If you mean professional photographers, I’m not sure if their numbers are shrinking, but they may be. It would be interesting to work out whether the invention of the snapshot in the 1890s meant that there was less demand for portrait photographers. My hunch is that there was less, though complimentary roles were also found for formal portraits and snapshots. What certainly did happen, and I think is happening today, is that people accepted a more informal sort of photography then. For example, with the development of portable cameras at the end of the nineteenth century you see a decline in the number of high quality, large format landscape photographs. Postcards tended to replace them. And now I suspect that postcards are being eclipsed by selfies and other self-made images that can be immediately posted on Facebook, Instagram, Snapchat, etc.

Does New Zealand have a distinct photographic tradition or style?

Yes and no. Photography has evolved here to serve the same needs and demands as elsewhere – for portraits, scenic images, and so on. And the nature of New Zealand, as a small country remote from other centres of the Western world, has meant that our photography has tended to follow models set elsewhere, but with less extensive development and often with a time-lag. Having said that, a visiting Japanese photography curator pointed out something to me recently that I hadn’t noticed. She was struck by how much of our ‘art’ photography seemed to be concerned with the past. Ann Shelton, Mark Adams, Laurence Aberhart, Ben Cauchi, Fiona Pardington… the list goes on. I said to her, ‘Isn’t it like that in Japan?’, and she said no, not in the least, and I realised that was indeed the case in most countries. I think this has something to do with our working through of post-colonialism in New Zealand.

If you had to choose a favourite photograph from the book, which would it be and why?

I can’t really pick one over another. However, for the sake of answering the question, one that I saw 30 years ago and had been in my mind to use one day is the James Parry photograph of Will Scotland’s plane flying at Otaki in 1914 on page 96 of my book. The aircraft is little more than a silhouette and looks like it would collapse into a pile of matchsticks in a gust of wind. The glass negative is badly deteriorated and a large piece has cracked off, its fragile state seeming to match the vulnerability of the aircraft in this pioneering flight. The dream of photography – to stop time and cheat mortality – is as poignant as the dream of flight, to escape our earthbound limitations.

What books are on your bedside table?

I don’t read in bed, so there is just Alan Watt’s 1957 classic The way of Zen, for dipping into if necessary. But my living room coffee table is weighed down with books to read, including Real Modern: Everyday New Zealand in the 1950s and 1960s by Bronwyn Labrum, Modern: New Zealand homes from 1938 to 1977 by Jeremy Hansen and Handcoloured New Zealand by Peter Alsop. I think I can see a theme there!

You might also like

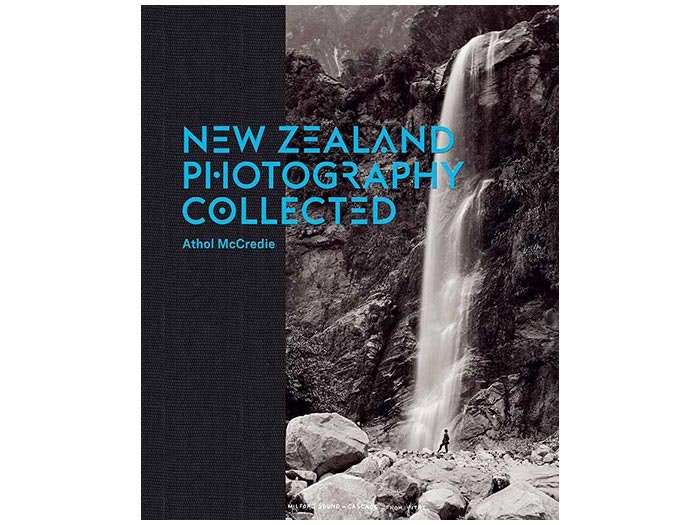

New Zealand Photography Collected

From the sublime to the surreal, the familiar to the forgotten and the 1850s to the present – see New Zealand photography like never before in this unique visual history.

Brian Brake: Lens on the World

The complete life and work of Brian Brake, New Zealand’s best-known photographer, has at last been encapsulated in one stunning book.