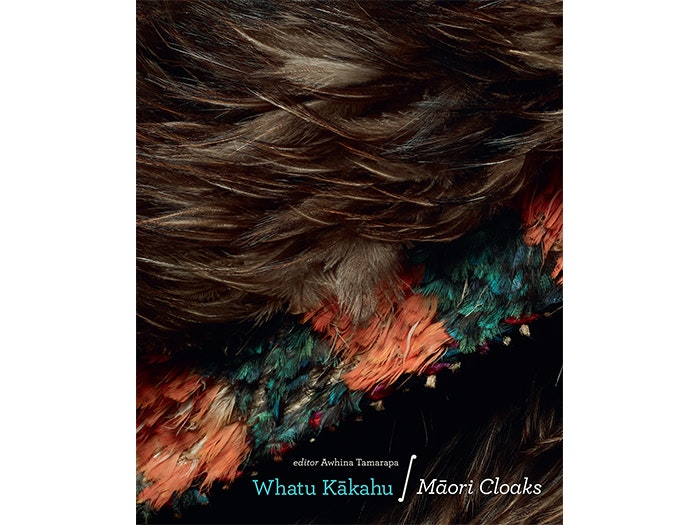

Whatu Kākahu | Māori Cloaks (Second Edition)

A celebration of the science and art of Māori weaving, focused on the largest collection of Māori cloaks in the world.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Awhina Tamarapa discusses the new edition of Whatu Kākahu | Māori Cloaks with Te Papa Press.

Awhina Tamarapa (Ngāti Kahungunu, Ngāti Ruanui, Ngāti Pikiao) holds a Bachelor of Māori Laws and Philosophy from Te Wānanga o Raukawa, Otaki, and a Bachelor of Arts from Victoria University, Wellington, where she majored in Anthropology. She has worked in museums for more than 10 years, including as concept developer and collection manager at Te Papa.

Photographed by Kate Whitley, 2018.

The book went out of print very quickly. It was concerning to receive constant requests to reprint. Thanks to persistent lobbying from different quarters, in particular from Mark Sykes, former Collection Manager Māori at Te Papa Tongarewa, Nicola Legat and the new Te Papa Press team, we have this amazing opportunity to publish an up-to-date edition.

Kataraina Hetet, one of the weavers interviewed in the first book, is quoted; ‘It’s so important for the world to know that not only is there a catalogue of all these cloaks, but there is the knowledge, the meaning, that gives them value.’ Her thoughts express why we produced the book in the first place. It is also why it is critical to keep a comprehensive, practitioner led resource such as Whatu Kākahu/Māori Cloaks in the public domain.

The book meets a continuing need. Its value is that it brings together a lot of in-depth knowledge on different aspects of Māori cloak weaving, based on the remarkable kākahu collection held by Te Papa. The chapter authors and the weavers who were interviewed for the original and new edition, have all contributed a tremendous wealth of information. With photographs, detailed technical descriptions, graphics, drawings, everything is in one resource for everyone, from people who are interested but know very little about Māori weaving to those who are practitioners and students.

Whatu Kākahu/Māori Cloaks is a resource that needs to be available to as many people as possible. This book demystifies some common misconceptions about Māori cloak weaving. As an example, a current issue and sore point for weavers is the indiscriminate calling every type of cloak a ‘korowai’. The recovery of the many beautifully descriptive names of kākahu and the profound language connected to weaving as a living art practice restores the dignity and value of Māori weaving. This book is part of the bigger picture of setting things right.

This was an opportunity to bring the book right up to date on topical and relevant issues. The new chapter focuses on some of the more contemporary acquisitions to the Te Papa cloak collection since the first publication, as well as highlighting practitioners who have researched early cloaks in Te Papa to recover customary knowledge. I also felt it was timely to introduce perspectives from Māori and non-Māori on aspects such as custodianship, access, collaboration and repatriation.

I’m currently carrying out a PhD with the Museum and Heritage Studies Programme at Victoria University of Wellington. My research explores the role of museums in the maintenance of Māori weaving as a living art practice. I’ve experienced projects involving customary weaving and other cultural practices that make a difference to peoples’ lives. As caretakers of heritage, museums have a responsibility to enable this to happen. The success depends on committed relationships with practitioners. This book is one such collaborative outcome.

It’s a strange mix of joy and sadness visiting ancestral taonga in museum collections overseas: elation in the actual reconnection, sorrow in the fact that they are far away from home, without our cultural presence to ‘keep them warm’. It was more than nine years since I last visited these museums. Many of the staff I met then were still there, which is good in terms of continuing relationships.

The kākahu in these museums are in various conditions of storage care and display. Some of the earliest cloaks collected on Cook’s voyages look as if they were woven yesterday. They are masterpieces, lying in drawers in a small room in an off-site storage building on the outskirts of London. The only full kākāpō feather cloak known resides in a museum in the historic riverside town of Perth, Scotland. This incredibly rare treasure would bring many to tears with its fragile beauty, dignity and understated status. Marischal Museum, University of Aberdeen, in the coastal port city of Aberdeen, Scotland, is the home of a whole store room of taonga Māori. That collection includes several kaitaka and korowai cloaks. Although closed to the public, this museum’s staff, like those at Perth, are progressive in their thinking regarding issues of repatriation and access to their collections by source communities and researchers.

Repatriation is not such a scary prospect for museums these days. Really positive repatriations of indigenous peoples’ heritage and human remains from museums and science institutions have happened of late and they have instigated powerful change in the hearts and minds of people in positions of authority. Building long-term relationships with these custodians is paramount in the reconnection of taonga. I believe we are experiencing a change in attitudes and ideas of what a museum is supposed to be and for whom. My view is that ‘ownership’ is a transitory concept. Māori people have an inalienable cultural and spiritual connection to ancestral taonga that can never be purchased or terminated. Museums have a role in mediating and realigning ethical change, for emancipatory and positive causes.

That story unfolded very quickly. We were lucky to find out about this as we only had a matter of days before going to print. The cloak was an image in Maureen Lander’s chapter on continuity of innovation in Māori cloak weaving. I read on social media that this cloak had recently been discovered by whānau back in New Zealand as belonging to their great grandfather. While searching online for examples of cloaks, one of the whānau came across the Melbourne Museum catalogue entry for the cloak. It had been in the museum collection since 1891. Although their ancestor’s name was misspelt slightly, this didn’t deter the whānau. They contacted the museum, who responded positively. Best of all the museum agreed to the ultimate return of the taonga to the descendants permanently. We made contact with Miriata Witika-Takerei, a great grandchild of Waata Tipa, the Ngāti Paoa ancestor to whom the cloak originally belonged, to make sure that we were able to inform the whānau about the book and the cloak’s inclusion with an updated provenance. It is a great example of a reconnection made, with museums acknowledging descendants and assisting this process.

Absolutely. Without a doubt, there are more weavers practising now then there were 50 years ago. The wearing of woven garments in kapa haka competitions, graduations, weddings and other occasions helps keep the art practice alive. There is also a definite diversity of practice. Weavers explore different mediums and platforms; digital, wearable arts, exhibitions, installation and sculpture. Weaving as a form of inspiration for artists and designers is ongoing. What I’d like to see more of is the recovery of ancestral knowledge informing contemporary practice.

All the kākahu are beautiful, for different reasons. They all have their particular qualities to appreciate and learn from. I have several favourites that fill me with awe and humility every time I open the drawers. The skill and expertise of our ancestors is incredibly uplifting. I have always admired the kahu kura woven by Makurata Paitini of Ngai Tūhoe, the story of ‘Piata’, the kahu huruhuru that belonged to Rawinia Ngāwaka Tukeke of Ngāti Kere, Ngāti Hinetewai that graces the cover, the historic kaitaka paepaeroa that belonged to Ruhia Pōrutu of Te Ātiawa, and the enigmatic kaitaka huaki paepaeroa we affectionately call ‘Webster 471’, that has served as a guide for Ngāti Kuia weaver Hamuera Robb’s journey of reconnection to the cloaks and taonga in Russia collected by the 1820 Bellingshausen expedition from Meretoto, Malborough Sounds. The stories and relationships to the weavers and iwi are powerful and enduring.

I have recently come to understand that the definition of ‘kaitiaki’, custodian, caretaker, is far more nuanced than the way we have tended to explain the term and operate as museum workers. This is exciting to me, as theory and practice is important to keep challenging us in moving forward.

Erenora Puketapu-Hetet wrote in her book, Māori Weaving with Erenora Puketapu-Hetet, first published by Pitman in 1989; ‘… weaving is endowed with the spiritual essence of Māori people. The ancient Polynesian belief is that the artist is a vehicle through whom the gods create.’ This book acknowledges and is dedicated to weavers past and present as the knowledge holders of this sacred art-form. It is an honour to be able to bring this book back into circulation.

A celebration of the science and art of Māori weaving, focused on the largest collection of Māori cloaks in the world.