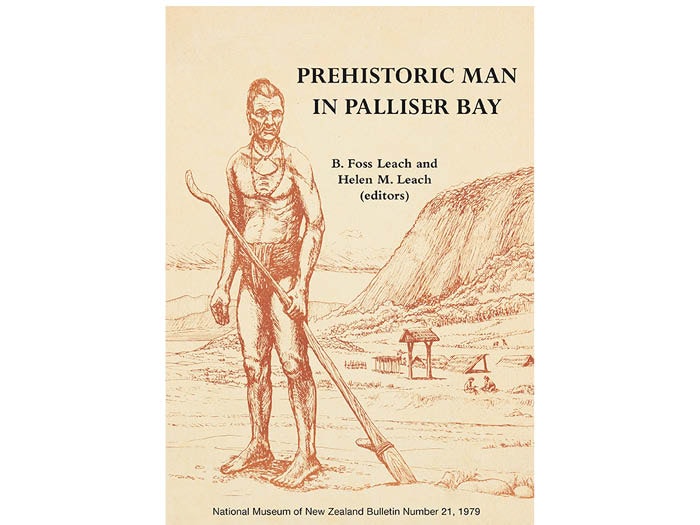

Prehistoric Man in Palliser Bay

Encountering 1,000 years of life in Palliser Bay

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Foss Leach discusses Prehistoric Man in Palliser Bay with Te Papa Press

Foss Leach CNZM is a New Zealand prehistorian. A strong advocate of collaborative cross-disciplinary research in archaeological science, he has published more than 100 scientific papers and books. He has contributed scholarly evidence to the Waitangi Tribunal for both the Crown and Māori claimants for hearings of Ngāi Tahu, Muriwhenua, Te Rorora and Ngāti Kahungunu ki Wairarapa. He has carried out archaeological fieldwork in New Zealand, Papua New Guinea, the Solomon Islands and Micronesia. In 1988 he founded the Archaeozoology Laboratory at the Museum of New Zealand and was its curator until 2001, when he retired. He has served as an officer of many New Zealand and international organisations concerned with archaeology and has held a number of honorary fellowships in New Zealand and abroad.

Helen Leach ONZM is an Emeritus Professor of Anthropology at the University of Otago and a Fellow of the Royal Society of New Zealand. She has a special interest in the anthropology of domestic life, including cooking and gardening. With her sisters Mary Browne and Nancy Tichborne, she has co-authored ten books on growing and cooking vegetables and on bread making. Her most recent book is Kitchens, a history of the New Zealand kitchen in the 20th century. She was awarded a Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture Medal for contributions in Garden History in 2008. In 2019 she became an Associate of Honour in the Royal New Zealand Institute of Horticulture (AHRIH).

Seeing this book back in print is unexpected but most appreciated. The Palliser Bay archaeological fieldwork represented three years of intermittent excavation of key sites, and even more time spent on laboratory analysis. Each of the authors of this Bulletin wrote their chapters based on their theses, both M.A. and Ph.D. The result was coordinated teamwork seldom evident in Aotearoa’s publications on prehistory at that time.

Palliser Bay has become a very popular destination, with many more visitors than it ever had in 1969–72, when the archaeology took place. People who have discovered its dramatic scenery and Māori sites are presumably keen to read about their prehistoric meaning.

It was a very important pioneering study in New Zealand, involving multiple different projects designed to explore many aspects of the life of the Māori people who lived in the south Wairarapa up to and including the early European period. The bulletin was written in the 1970s at a time when ethnologists and archaeologists argued vigorously about the identity of the first settlers, especially whether or not these people practised gardening of root crops, in particular of kūmara. Palliser Bay revealed evidence of the gardens of its earliest settlers at a time when their kin further south were still moa-hunters.

Those who took part still have vivid memories - we were excited about what we were doing. During the evenings in our quarters at Whatarangi we shared reports of what had been found that day, together with discussion of future directions. This co-ordination enabled us to write the prehistory of the eastern coast of Palliser Bay.

Prehistoric life in Palliser Bay was far from easy - these people had to work hard under sometimes difficult conditions, as did pre-European and historic period Māori in other parts of the country. ‘Nasty, brutish and short’ is often used to describe prehistoric life in many parts of the world. The Palliser Bay people had relatively high infant mortality and short life spans, even though they had access to gardening land, and forest and marine resources. Most of the sites that were studied represented small, early coastal villages and camps set amongst gardens and simple storage pits. These were occupied before the appearance of fortified pā some centuries later. The pā were constructed on steep ridges overlooking the coast. Storage pits were often fortified, or hidden, and usually surrounded by a raised rim. Clearly, the residents were concerned about their safety. During the centuries of occupation in Palliser Bay, environmental change added to the impact of human fires and cultivations at the base of the foothills. Eventually the people concentrated on the lower reaches of the Ruamāhanga where large, heavily fortified pā were erected.

The public and academic audience were informed of the research results of the Palliser Bay expedition by television interviews, newspaper reports, the Museum Bulletin, and articles in scholarly publications such as the Journal of the Royal Society of New Zealand. Sadly, there have been very few comparable multiple disciplinary projects in New Zealand. The growth of ‘contract archaeology’ (rescue excavation on sites about to be destroyed) has kept many archaeologists busy at the expense of pure research.

The Palliser Bay research was carried out with full support of local iwi authorities. All have maintained a keen interest in the archaeology of their region. Today, they are interested in developing tourism ventures for the area, using the reprinted Bulletin as a resource.

There are always new developments in archaeological technologies, such as remote sensing and improvements in methods of dating. It is hoped that more research will be carried out in this region in the future to expand on the knowledge of pre-European life.

The research covered by the National Museum Bulletin was largely focussed on Palliser Bay. Since the project ended, greater interest is now being given to the movement of Māori in the early historic period into the main Wairarapa Valley.

There is always scope for new investigations - to refine and improve existing knowledge and respond to unforeseen new chance discoveries. The South Wairarapa has many wetlands close to early historic Māori settlements. These contain valuable wooden artefacts such as carvings that are protected by being waterlogged. It is imperative that such cultural deposits are properly protected for posterity; however, many are under constant threat from land development.

Encountering 1,000 years of life in Palliser Bay

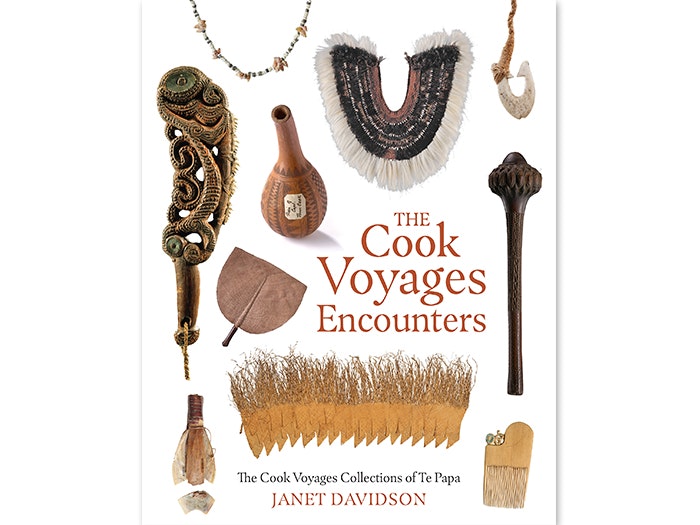

A comprehensive guide to the objects associated with the voyages of James Cook held at New Zealand's National Museum