A Man Holds a Fish

Haunting portraits by one of New Zealand’s finest photographers.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Glenn Busch discusses A Man Holds a Fish with Te Papa Press.

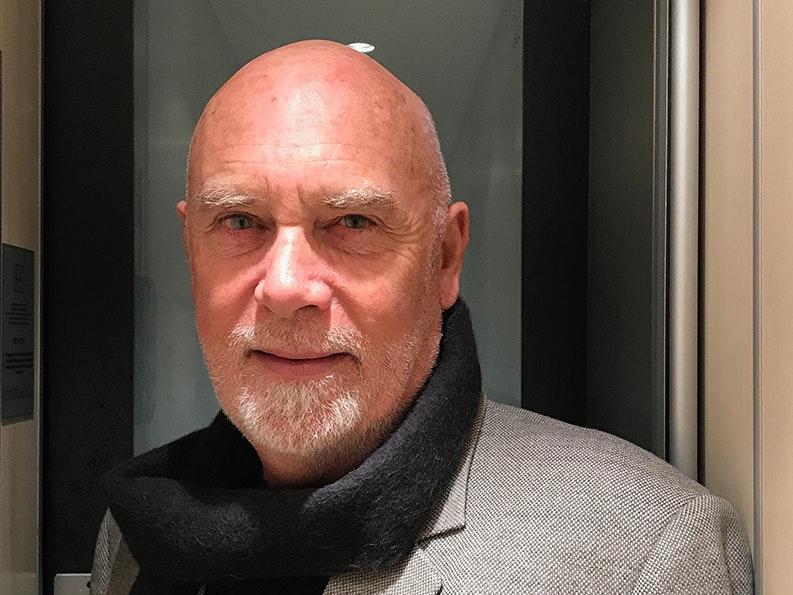

Glenn Busch, best known for his intimate, thought-provoking portraits and captivating social documentary work, was born in Auckland in 1948. He left school at 14 and spent his early years working as a manual labourer in many different places around Australia and New Zealand.

Throughout his career, Busch has focused on capturing the essence of daily life, often exploring themes of community, work and identity. His influential projects include Working Men, You Are My Darling Zita, The Man With No Arms and Other Stories, My Place and the ongoing Place In Time documentary project.

Glenn Busch. Photo by Trish Allen

Intuition comes first. Then I have a think about it. They are the images that for me show most strongly something of the lives of the people I have photographed. They were made to show life at that moment, as I saw it in front of me, with as much honesty as possible.

Most important should be an immediacy, a certain vitality that connects with the viewer. What makes that possible is the success of the collaboration. The importance of mutual respect. In the making of these photographs there are one or more people involved beside me. Their trust and willingness to declare themselves in their own particular way, to be alive, is of vital importance. It is what makes the image work or not. My only task is to be aware, in one brief moment, of the possibility of that person’s story. Or at least, a small part of it.

One other aspect of my responsibility is an awareness of the environment in which the photograph is made. And also such things as the clothes people are wearing, how they wear them, how they have chosen to place themselves before the camera etc. I use the usual tools – light, point of view, composition, frame, depth of field and so on – but while I select the way in which these tools are used, nothing is staged or falsified.

First of all, yes, because they are obviously portraits I have made and like, but also because they are images from my life and times and so have a number of other personal meanings for me, meanings that they wouldn’t have for say, my children or grandchildren. That is obviously not to say that images from another time have no effect on us today. Some of my own favourites are found among the so-called Fayum portraits. Made to be attached to the mummy of the person portrayed, they were painted using coloured beeswax in the first to third centuries.

All lives have some degree of sadness in them at some point. Sometimes collectively, as in war, famines and other sorts of disasters. Sometimes it is more personal. There are some images that show people who may have had to deal with difficulty in their lives, but that does not necessarily mean they should be described as sad. There is a complexity to all human emotions. Certainly, none of these images should be construed to have been made out of pity.

Yes, in many of the portraits there is an awareness of many of those strong human traits – fortitude, strength of spirt, courage, forbearance, determination to endure and so on.

His photographs were simply the first I saw that seemed real to me. They could have been by any number of photographers I later admired, but his happened to be there that one particular day when I walked into the Auckland Art Gallery and saw them.

One particular image I liked a lot was of a woman known as Miss Diamonds. She covered herself in costume jewellery and apparently told stories, or your fortune, in return for a glass of wine. Brassai met her only once, the day he made the picture, but many years later, while hanging an exhibition of his work, an old man appeared to say he had been her lover and would Brassai like to hear her story. Of course he would! Three days later he went to see him at his apartment. At the door to his building, he was asked by the concierge if he was a member of the family? No, he told her, but I have an appointment to see him. That would not be possible, she told him. Sadly Monsieur has died, just yesterday, in the afternoon.

Thinking of that story again, it makes me realise how looking back I feel much the same way. While I often talked at some length with the people I met and photographed, sometimes for hours, it was not until the 1980s that I started to record and write down the things people were saying to me. Stupid.

Far from shocking, those situations I found myself in at the time seemed very ordinary to me. It was the lot of many people in my generation. The photographs I made of working men, and most others as well, came simply from my own experience of growing up and living among these people. And of course, my own early experience of working in sugar mills, factories, mines and so on. The men I worked alongside, unlike me who moved on every few months, managed to put up with demanding, difficult, sometimes boring and too often dangerous jobs year after year in order to feed and look after their families. They were men I developed a great respect for, which is no doubt why I have so often tried to record their stories, both in image and text. Of course, just as remarkable were the women, the partners of those men, who managed to feed, clothe, cook and hold households together on what was sometimes very little. Others have told their story.

There was I suppose a financial discipline. I never made any money from the type of work that I was doing in photography, and film was not cheap. In one way that was a good thing. There was space for twelve negatives on a roll of 120mm film and for thirty-six on a roll of 35mm film. It instilled a certain control in the number of images I might make at one time. Sometimes just the one, and usually no more than three or four. The good thing about that was how it forced me to think more intelligently about the making of the photograph – compelled me in fact to see what I was actually looking at. It also encouraged a careful analysis of the resulting proof sheet. I can’t say I miss the hours spent in a dark room amid the smell of chemicals. There was something, however, that was rather special. The excitement of seeing a significant image start to materialise in the tray developer. I sort of miss that.

No, everyone is different and unique. All of the people in this book are special in their own way. With very few exceptions, I felt myself extremely lucky to have spent so much time in my life with people I wouldn’t ordinally have had the chance to know and talk with.

Certain aphorisms are often suggested as advice to would be writers – ‘write what you know’, ‘show don’t tell’, ‘less is more’ and so on. Such advice sits well within other areas of the arts, including photography. My own work reflects that idea.

Most often the people I have photographed were the sort of people I had grown up around, often reminding me of a grandparent, a friend from childhood, or simply someone who lived on the streets I grew up in.

While the photographs people make inevitably say something of themselves, what’s obviously most important in the work I do, both with image and text, is the person or people whom the work is about. All my work is about people, it has never been anything else, and as such it is always a collaboration. The most important input comes from their side of the camera.

I guess so. As I mentioned earlier, we are all unique in ourselves and we bring that uniqueness to whatever it is we look at, read or listen to. Put our own spin on it, so to speak. For myself, if I find I have any sort of interest at all, trying to go beyond simply saying I like it, or I don’t like it, is a good start.

The work I have made comes from my own compulsion to make it. It draws from my own experience as opposed to work made for other reasons. I was always pretty hopeless at doing work on assignment. The few times I tried it didn’t work out so well.

As an example, I was once given a job by The Listener to photograph various vineyards around Auckland. Unfortunately I was put into a bus along with ten or more seasoned journalists, who very quickly took full advantage of the samples on offer. I resisted at first, at least until the second venue, where I ended up doing much the same.

Of course the next morning they could just make it all up. I wasn’t able to do the same with the embarrassing photographs I, shamefaced, handed into the office. I was offered no other work with The Listener for some time.

Then one day, probably unable to get anyone else, they asked me to go downtown and photograph the then prime minister of Australia Bob Hawke, who was on a visit to New Zealand. A simple portrait, can’t go wrong. Bob wasn’t drinking at the time but insisted that I shouldn’t feel obliged to do the same and kept filling my glass with the complimentary whiskey the hotel had laid on. I think that was the last job I did for them.

Haunting portraits by one of New Zealand’s finest photographers.