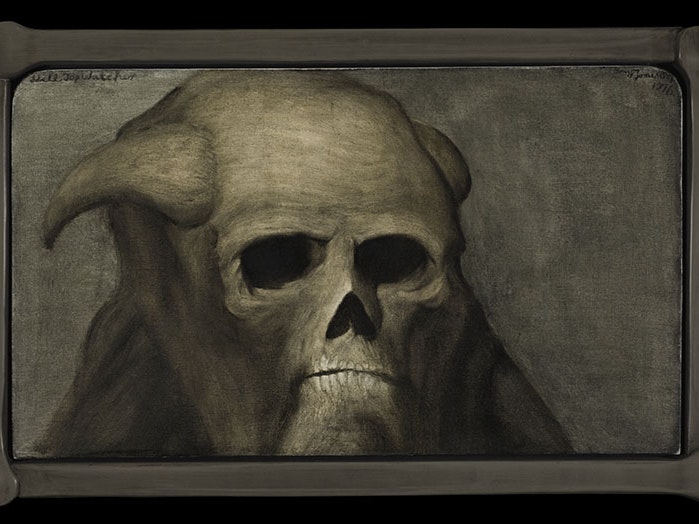

Tony Fomison: Lost in the Dark

An exhibition of Tony Fomison’s paintings, featuring monsters, misfits, and medical deformities that explores what it means to be an outsider.

Closed

18 Aug – 4 Nov 2018

Exhibition Ngā whakaaturanga

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

What does female sexuality look like in art? Here, it looks like monsters, mermaids, and minotaurs…

In this online exhibition, Te Papa intern Rata Holtslag picks ten works from Te Papa’s art collection that use strange monsters and dark creatures to explore themes of women’s desire, sexuality and power.

An exhibition of Tony Fomison’s paintings, featuring monsters, misfits, and medical deformities that explores what it means to be an outsider.

Closed

18 Aug – 4 Nov 2018

Exhibition Ngā whakaaturanga

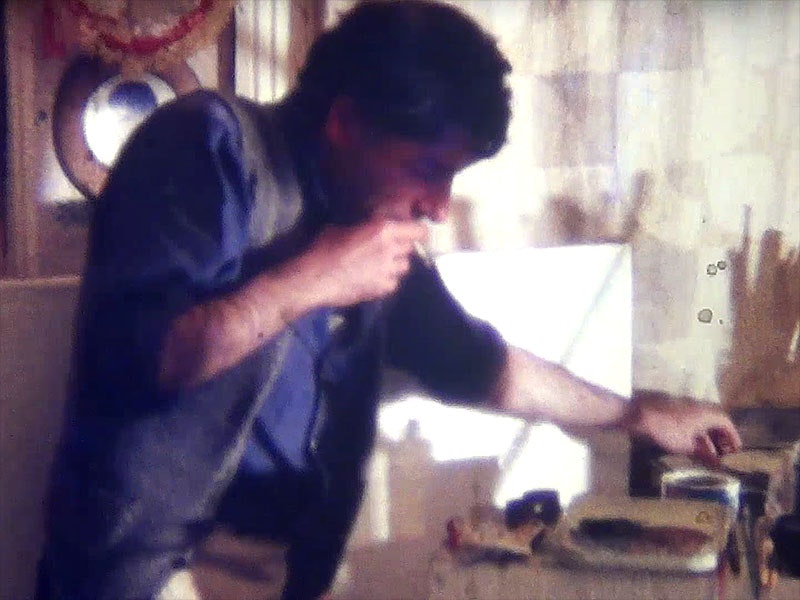

See rare footage of Tony Fomison at work, captured on glorious Super 8 by New Zealand experimental film-maker Martin Rumsby.