Crustaceans: The Swiss Army knife of life

Crustaceans are like the Swiss Army knife of life, revealing an appendage for any occasion. Multifunctionality is the crustacean M.O., with their limbs cleverly turning to just about any task.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

All animals, human beings included, rely on other animals for survival, forming relationships of symbiotic co-existence. But some creatures take this reliance to ghoulish heights. We call them parasites.

The translucent salp glides gracefully through the water column, drifting this way and that, its gelatinous form at one with the sea’s currents. Little does this salp know that its fate lurks in the deep dark. Emerging from the gloom is an alien-look-alike known as Phronima.

Phronima nestled insde its hollowed-out salp home. Photo by Mike Stukel CC-BY

The equipped nightmarish species of Phronima enters the salp and claws its way into the body, hollowing out any organs and making extra space. Once inside, the Phronima sets about devouring its new host from the inside out, eviscerating the salp, bar its outer layer. Satisfied, the mother-to-be lays eggs in the hollowed encasement.

The salp’s corpse has yielded the perfect incubator-pram-in-one. The Phronima pushes this “pram” around until their eggs hatch. The newly hatched young aren’t eager to leave the home comforts of the salp, as nutrients flow inside of their own accord keeping the spawns’ hunger satiated.

Not all parasites kill their hosts so spectacularly as the Phronima does, some are more subtle in their approach, cleverly keeping their host alive so as to mooch off of it for longer.

Have you ever sat down eager to demolish a dish of steaming mussels, only to open one and find a teeny tiny crab inside? This is the pea crab, and it has been siphoning food from that mussel its entire adult life.

A pea crab in an oyster by Lena Struwe via iNaturalist CC BY-SA 4.0

The armoured shell of the mussel, usually triumphant in keeping out unwanted predators, is breached by one of the smallest known crab species. As the filter-feeding mussel sucks in bits of food from the water, the larval crab glides on in unnoticed. The mussel’s armour now becomes the crab’s armour. In fact, female pea crabs never leave and so will never find the need to develop a hard shell, as other crabs do.

Settled within the lip of the mussel, all the crab must do for food is wait for its host to filter some inside. The pea crab is predictably pleased with its homey host. At least right up to the moment you catch its nice lodging and cook it!

But this relationship is not without its dangers for the crab. The dedicated male crab will do anything to reach its immobile mate. It will even perform the perilous act of darting in and out of the mussel. If they aren’t speedy enough, they will find their limbs severed by the crushing jaws of the shell.

The mussel does not die, but it can’t grow to its full potential either. The crab thrives gleefully while its host suffers silently.

Further still, there are parasitic crustaceans who do not kill their host like Phronima but aren’t exactly subtle like the pea crab. This leads to the final freaky fiend: the tongue-eating louse (Cymothoidae spp.).

Flowing through the gills of a worthy host the tongue-eater begins its journey. Once inside the fishes’ mouth, the tongue-eater does the truly repulsive. Yes, you guessed it, it begins munching on its host’s tongue. The unwitting fish host is helpless as the tongue-eater sinks its vampire-like mouthparts into the tongue and drains it of blood.

Tongue-eating louse (Ceratothoa italica) in a bogue. Photo by Lutz Popper via Flickr. CC BY-NC-SA 2.0

The tongue eventually shrivels and dies, leaving the perfect space for the glutted tongue-eater to latch itself. The fish can now freakishly use its new tongue to swallow its supper quite normally. The resident tongue is contented too, feeding off blood left in the mouth. The tongue-eater will stay put for mating too, happy to house its young until they are ready to begin their own parasitic journey.

You may think just one species has become this freaky, but there are over 100 species of tongue-eaters out there, fishes beware!

Rhizocephala (translated as ‘root-head’) are derived barnacles that parasitise mostly decapod crustaceans, but can also infest Peracarida, mantis shrimps, and thoracican barnacles and are found from the deep ocean to freshwater. They have lost nearly all of their external morphology, most of their body grows inside a host crustacean.

A bit like an animal version of a mushroom, the animal spreads as a network throughout the host. The reproductive organ is called the ‘externa’ and forms on the outside, eg under the tail of the crab.

The externa down near the tail and the root system of a Sacculina from a crop of Cirripedia by Ernst Haeckel via Wikimedia Commons. Public domain

Roots can often be seen extending to the brain and central nervous system, which could help explain how parasites like these can manipulate their hosts' behaviour.

Most copepods are free-living, but these parasitic barnacles attach themselves to a fish and anchor themselves into their skin, extracting nutrients from their host.

Parasitic copepods are vastly different in appearance from other crustaceans. In general, adult parasitic copepods are shapeless, having neither limbs nor antennae and sometimes no body segments.

Parasitic copepods on the side of a fish.

Because these creatures start their lives as free-living animals, scientists infer that their ancestors were free-living and that they only evolved parasitic behaviour after their environments dictated it.

Are these freeloading creatures the villains? Or are they simply super-savvy survivors?

This page was developed in association with NIWA Taihoro Nukurangi.

Crustaceans are like the Swiss Army knife of life, revealing an appendage for any occasion. Multifunctionality is the crustacean M.O., with their limbs cleverly turning to just about any task.

Crustacea includes lobsters, crabs, shrimps, prawns, hoppers, wood lice, water fleas, and several other groups. Most crustaceans live in the sea but some are found in freshwater or on land. The one thing they all need to survive is water, or at least a moist habitat.

Primary

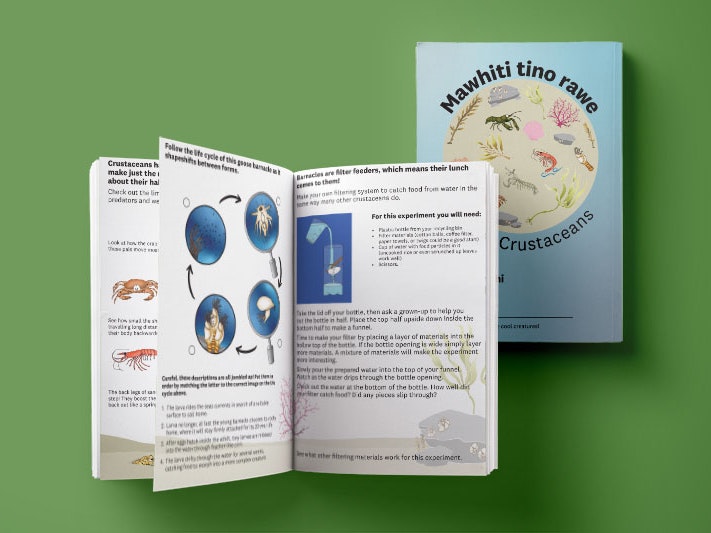

Crustaceans come in all shapes and sizes – from huge king crabs to tiny sand hoppers! Get to know them through movement, storytelling, puzzles, and more!

Activity book