One especially interesting account of the use of metal uhi occurred with the tattooing of Iwikau Te Heuheu of Ngāti Tūwharetoa (Taupō district) in 1841. The operation was witnessed by Edward Jerningham Wakefield of the New Zealand Company, who commented:

‘The instruments used were not of bone, as they used formerly to be; but a graduated set of iron tools, fitted with handles like adzes… The man spoke to me with perfect nonchalance for quarter of an hour, although the operator continued to strike the little adzes into his flesh with a light wooden hammer the whole time, and his face was covered with blood.’ [Edward Jerningham Wakefield. Adventure in New Zealand from 1839 to 1844. Whitcombe and Tombs Ltd, Wellington, 1908, p.425]

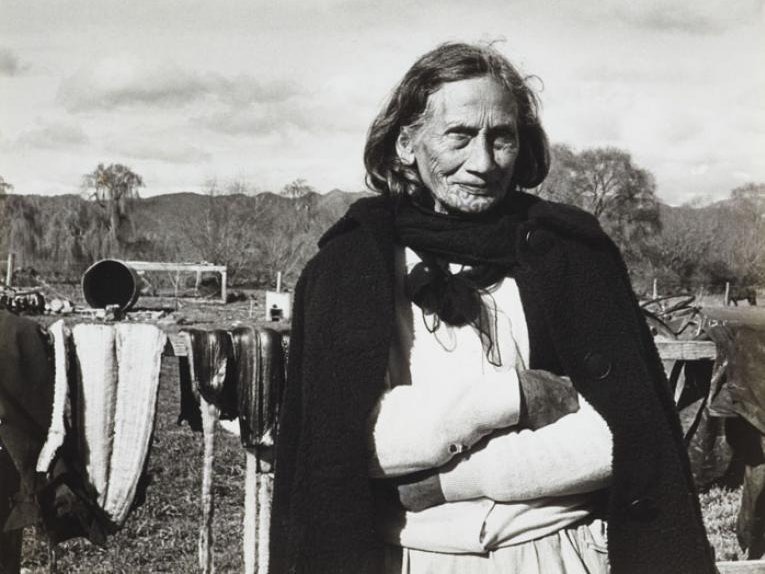

But perhaps the biggest shift in practice was the adoption of needle tattooing during the late 19th century and early 20th century. The use of grouped needles became the most common form of tattooing throughout the world during this period, and it was the form most commonly applied to pūkauae, the female chin tattoo, in the early 20th century. It’s still the most ubiquitous form practised in the world today.

Reclaiming moko

The ever-decreasing generation of kuia moko inspired a young group of artists and carvers following the protest movement of the 1970s to reclaim moko as a unique expression of Māori identity.

Combined with the interest of academics like Michael King and the continued popularity of the published works of Gottfried Lindauer and Charles Frederick Goldie, and colonial artists like George French Angas, it helped reawaken the interest of a new generation in this venerable and unique art form.

The 1980s saw the rebirth of moko, but it wasn’t until the 1990s that it really started to gain any real currency as an authentic artistic form and contemporary cultural practice.

But it really hit its stride in the 2000s. In the course of a single generation, a dedicated group of determined and courageous tohunga tāmoko (tattoo experts) and tattoo practitioners reclaimed and revitalised the cultural practice of tāmoko. A continuously growing demand from young Māori and not-so-young Māori has ensured that moko is now an increasingly seen and accepted part of mainstream Aotearoa New Zealand.

Toi Tuku Iho - Tā Moko and Tatau, 2021. Photo by Te Papa Public Programmes. Te Papa (181139)

![A Good Joke (All ‘e same t’e Pakeha) [Te Aho-o-te-Rangi], 1906/1921, Auckland, by Charles F. Goldie. Purchase 2020. Te Papa (2020-0025-3) A painting of a man who has a facial tattoo and is wearing a bowler hat. The painting is in a frame that has Māori carving on it.](/assets/76067/1755663755-ma_i636407.jpg?ar=1.3333333333&fit=crop&auto=format)