Missionary impact

From 1814, Christian missionaries from Britain began building up friendly relationships with Māori. Mutual trust grew, and eventually this helped the British government gain influence here.

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

Open every day 10am-6pm

(except Christmas Day)

Free museum entry for New Zealanders and people living in New Zealand

One item the Pākehā visitors brought caused more upheaval than any other – the musket. At the start of the 19th century, these guns were the norm on European battlefields.

Nā te pū ka toa tētahi, ka taurekareka tētahi.

The musket determined who was warrior and who was slave.

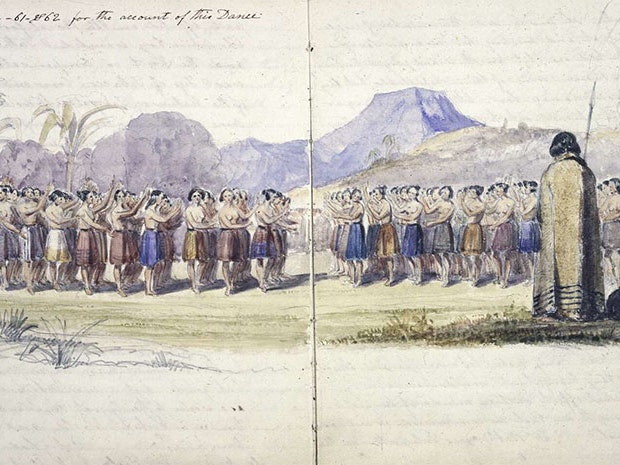

War dance, New Zealand, about 1845, by Joseph Jenner Merrett, watercolour. Rex Nan Kivell Collection, National Library of Australia (PIC Drawer 12898 #T2783 NK1272)

Muskets were unknown to Māori, who fought with weapons such as taiaha and mere.

The rangatira who came across muskets in their dealings with Pākehā realised the enormous advantage guns could give them over enemies with customary weapons. The musket’s power lay not only in the damage it could inflict, but also in the fear it instilled.

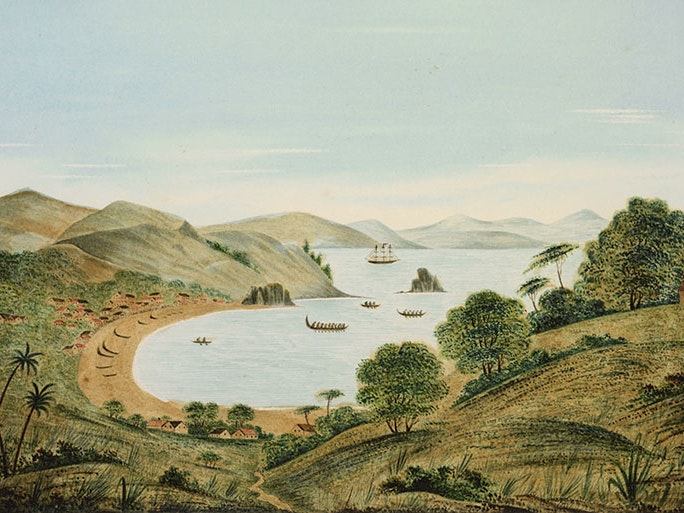

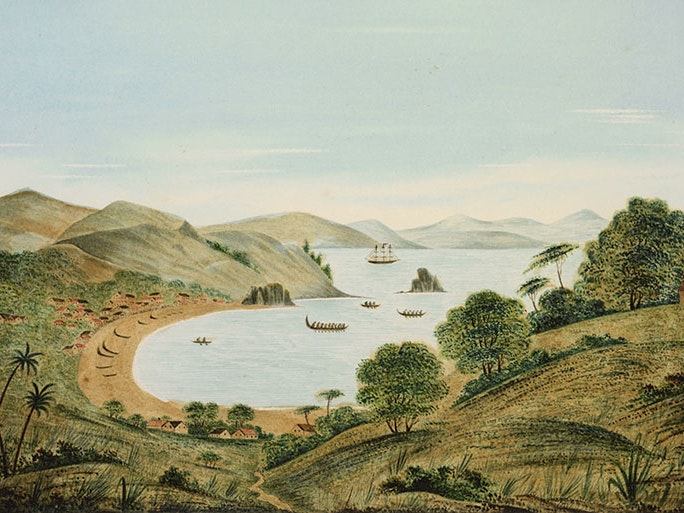

Louis Auguste de Sainson, Defrichement d’un champ de patates, 1839, engraving. Alexander Turnbull Library (PUBL-0034-2-387)

Muskets meant defeating enemies and gaining or successfully defending territories and resources. Rangatira were willing to pay a premium for these weapons. They traded large quantities of flax fibre and food supplies for muskets.

Ngā Puhi had the most guns at first and attacked tribes as far south as Cook Strait. They took increasing numbers of captives who were then kept as slaves to produce more goods to trade for more muskets.

Māori war dance, 1834, by Edward Markham, ink and wash. From Markham’s New Zealand or Recollections Of It, holograph, p.53. Alexander Turnbull Library (MS-1550-053)

A musket wasn’t a one-off purchase. Once you had one, you needed a reliable supply of ammunition – gunpowder, as well as lead for musketballs. Māori needed to form relationships with Pākehā who could supply ammunition and, if needed, repair guns.

As more tribal groups gained muskets, a time of bloody upheaval followed.

The arms race between tribes escalated until almost all had muskets, leading to uneasy truces between the various groups around 1830. By then, however, some tribes had been decimated and others driven from their lands. Tribal boundaries across the North Island had been changed for ever.

One tribe to influence the redrawing of tribal boundaries was Ngāti Toa. The tribe had battled for years with neighbouring tribes for control over the rich resources of Kawhia Harbour. Te Rauparaha, a Ngāti Toa rangatira, led his people on a great migration – from Kawhia, south to the Kapiti region.

There, he knew, they’d find plentiful land and resources, and greater opportunity to buy muskets. And from this lower North Island base, his tribe would also come to dominate the upper South Island.

***

This content was originally written for the Treaty2U website in partnership with National Library of New Zealand Te Puna Mātauranga o Aotearoa and Archives New Zealand Te Rua Mahara o Te Kāwanatanga in 2008, and reviewed in 2020.

From 1814, Christian missionaries from Britain began building up friendly relationships with Māori. Mutual trust grew, and eventually this helped the British government gain influence here.

Before 1840, the British government had no legal power to protect its citizens while they were in New Zealand – nor could it make unscrupulous ones obey British laws. This was a problem. Māori, British traders, and missionaries all expressed their dissatisfaction.

Polynesian people stepped onto these shores some 800–1,000 years ago. Over the following centuries, this country was a place of independent tribal groups who looked after their own territories and lived close to the land, physically and spiritually. Eventually every part of the country was overseen by a particular iwi or hapū, each led by their own rangatira.